A history of invisible conflict

When we started working in marine conservation in the early 2000s, we quickly realised that data is an essential tool to help us understand the state of our fisheries and marine ecosystems. We focused mainly on fisheries in Kilwa District, Tanzania, where controlled open-access fishing is common. Controlled open-access fishing is a fishery management method that occurs with minimal restrictions.

At that time, fisheries management in Tanzania used a top-down approach to decision making where the government developed laws, regulations, and other management tools with limited community participation. In recent times community participation has increased, and the communities themselves have led up enforcement of these rules. However, several issues, including access to decision making processes and finances, affect the engagement of communities in management, leading to conflict between fishers (the community) and resource managers (the government).

Over the years, illegal fishing became rampant, despite the efforts by conservationists and the government to change the situation. The situation was also not favoured by the fishing grounds’ scale, size, and accessibility. The lack of data on incidences of illegal fishing compounded the issue, making this problem invisible to many.

To minimise the incidence of illegal fishing, we began advocating for greater community involvement in data collection and fisheries management. This started with the formation of Beach Management Units (BMUs) to enhance fisheries co-management. BMUs are locally led groups of fishers, fish processors and traders, boat owners, and other stakeholders who depend on fisheries for their livelihoods.

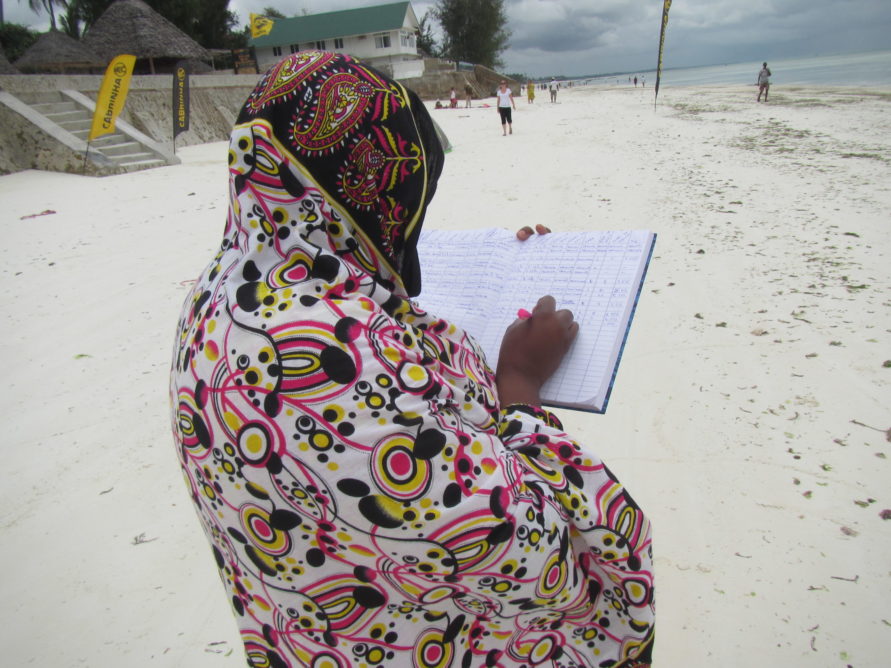

BMUs were first established in Mafia, Rufiji, and Kilwa districts, followed by a formal fisheries co-management plan in Tanzania in 2009. Somanga district then formed its BMUs, and the community started collecting fish catch and surveillance data. Data collection has since graduated to using mobile applications, a shift from the paper records used in the past. But is data enough?

Data is present, but not enough on its own

We learnt over the years that data is meaningless if management and communities do not make use of it. Clearly, training communities to interpret the data would make it more valuable for fisheries management. For instance, when communities began collecting and analysing data, they discovered that fishers from Kilwa primarily targeted the more abundant rabbitfish (tasi).

The data also showed that emperor fish (changu) had a higher market value, so they refocused their fishing efforts to target the higher value catch leading to overfishing. This data helped inform management while involving the community through co-management approaches.

Understanding the data has also given communities a chance to participate in decision making at a time when coastal communities continue to depend heavily on the ocean. The data, therefore, makes it easier for communities to engage with and be respected partners in fisheries management.

In addition to fisheries data, socio-economic data collected throughout the years from communities in Kilwa reveals that communities engage in other income-generating activities. Notably, fishing is male-dominated while women engage in subsistence agriculture and fish processing.

Other activities such as seaweed farming have become less lucrative due to unfavourable weather conditions, but the community in Pombwe is keen to try seaweed farming soon as conditions stabilise.

What next?

After interacting with communities, we now understand the challenges communities face in collecting and using data for decision making. Due to lack of resources, data collected remains unprocessed in some cases, and fishers cannot test the validity of the data collected. However, as we continue to work with communities, we seek to motivate them through training on analysis and reporting to increase ownership of the process.

Training community members in primary data collection and processing techniques will increase their understanding of data. Our long-term goal is to see communities use data actively and independently to manage their fisheries and contribute to the advancement of ocean literacy and conservation.

By Haji Machano and Khamis Juma – Regional Partner Support Coordinators, Tanzania.

Please access our data training toolkit here.

Hello Haji,

Good work you doing!

I am Peter Britz, a professor of fishery science at Rhodes University. I am working with FAO/SWIOFC to recommend an approach to improving management of the sea cucumber fishery. I think building fisher institutions and empowering fishers to participate in managing the fishery and obtaining more value from their products is a key strategy. Do you have any information on your work, advice and so on.